Introduction

“Effective communication following a cyber security incident forms a critical element of the activities needed to protect your company’s customers, stakeholders, and reputation more generally.”

– Richard Knight and Jason Nurse.[1]

This framework supports organisations with their public-facing communications during a cyber security incident.

It helps you decide when to communicate, who to communicate with, and how much to share – as part of your wider incident response plan.

Create an incident response plan – Own Your Online External Link

Communication is often overlooked during incident response, with teams focusing first on the technical fix. But how you communicate – both during and after the incident – can shape how your organisation is perceived.

You need to strike a balance between:

- giving stakeholders, members, customers, and the public clear information on what the incident means for them and what actions to take, and

- protecting sensitive details that could help attackers or make the situation worse.

What to do when an incident occurs

Initial steps

As part of your incident response plan, nominate a Communications Lead (Comms Lead). This person is responsible for approving all messages shared with internal and external stakeholders, including media and the public. The Comms Lead may still report to a wider leadership group, but they are the final sign-off for communication.

Who your stakeholders are will vary depending on the situation – this might include internal staff, external partners, or the public.

Key decisions

The Comms Lead needs to make three key decisions.

- What information needs to be communicated, and when?

- What regulatory disclosures are required?

- Which audiences need which information?

These decisions are supported by information gathered as part of the broader incident response plan.

Information gathering

The Comms Lead will need to gather the following information from the incident response team as early as possible.

- What type of incident has occurred?

- Who is affected (for example, clients, agencies, the public)?

- How widespread is the incident (for example, is it local, regional, national, international)?

- Is there an immediate risk to others?

- Is the incident ongoing or contained?

The Comms Lead should also check for the following developments.

- Is the incident being reported publicly or on social media?

- Have clients or users reported it to you?

- Has the attacker contacted you or made themselves known?

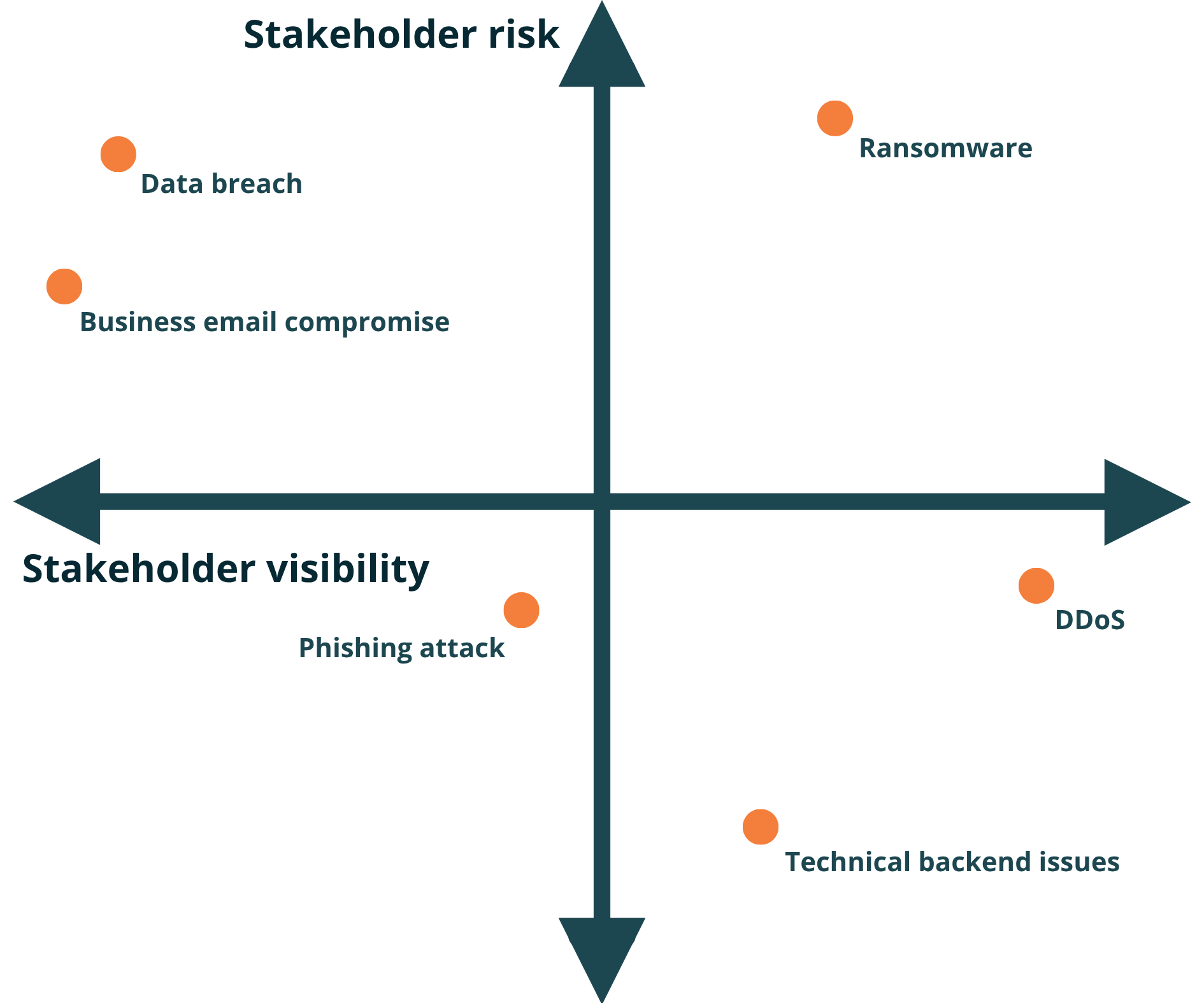

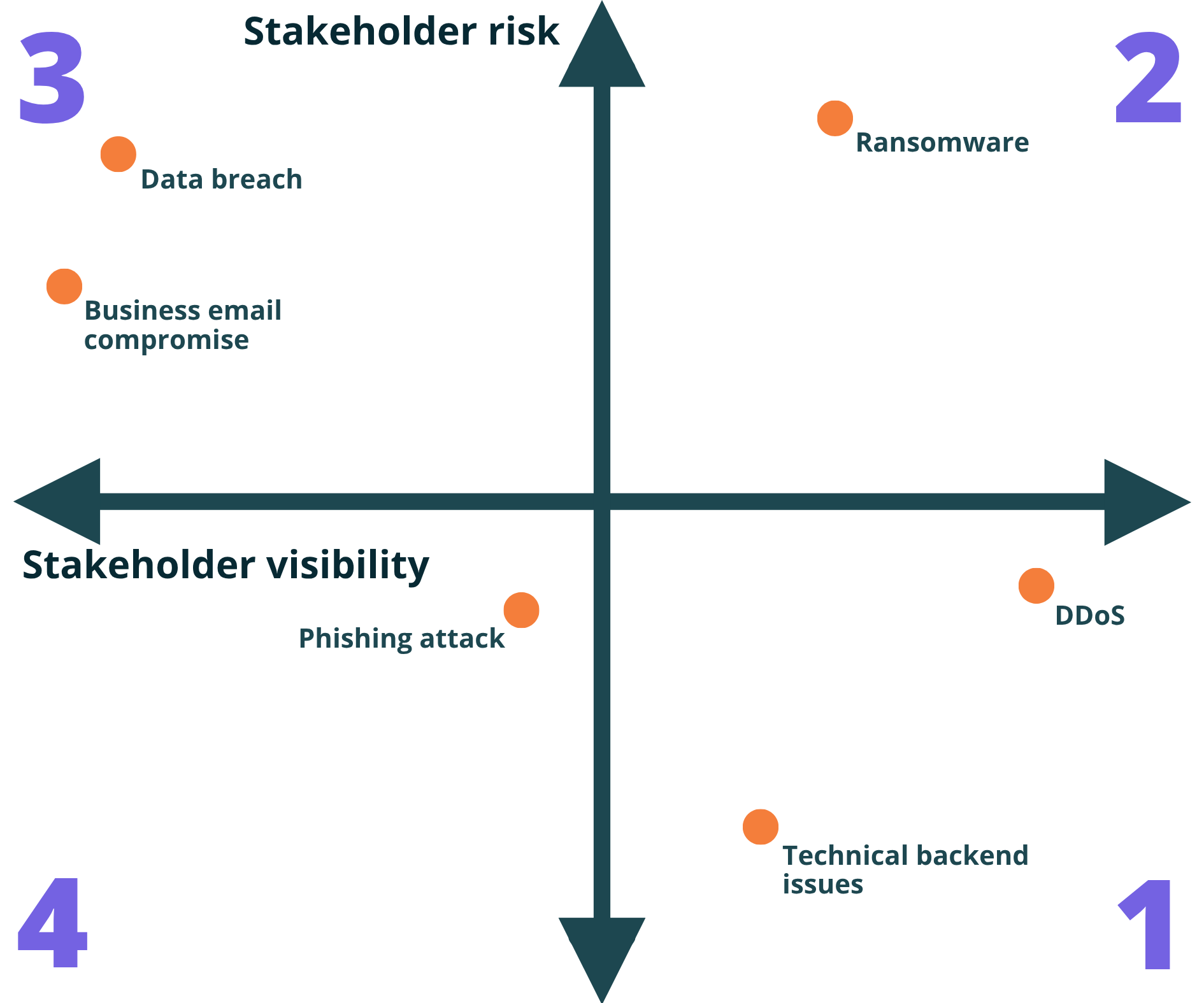

Stakeholder risk and visibility matrix

This tool helps you decide your messaging priority based on the risk to stakeholders (vertical axis) and visibility of the incident (horizontal axis).

What you don’t know can be just as important as what you do. At the start of an incident, some key details are likely to be unknown – and that’s okay. Make a note of any gaps in information. As the situation develops, new details will emerge that may change how you respond.

What information needs to be communicated, and when

Some information must be disclosed immediately to authorities. Other communications can be delayed – depending on the incident.

Messages should be created quickly but thoughtfully. Rushed statements can create confusion or alarm.

Responsibilities

Disclosures to regulatory bodies (such as NZ Police, The Privacy Commissioner, other government agencies, or NZX) may be required. While these actions may not be handled by your communications team, the Comms Lead must be informed so stakeholder messaging is accurate and consistent.

New Zealand laws

The Privacy Act states “Under the Privacy Act 2020, if your organisation or business has a privacy breach that either has caused or is likely to cause anyone serious harm, you must notify the Privacy Commissioner and any affected people as soon as you are practically able.”

Privacy breaches – Office of the Privacy Commissioner External Link

The term ‘serious harm’ can seem unclear. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner provides examples, including:

- physical, psychological, or emotional harm or intimidation, and

- financial fraud including unauthorised credit card transactions or credit fraud.

The NCSC recommends reporting all breaches – or potential breaches – regardless of how serious they appear. Transparency builds trust with stakeholders, even in minor cases.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner expects to be notified of breaches no later than 72 hours after your organisation becomes aware of it. You can report a breach using the privacy breach notification form.

Privacy breach notification form – Office of the Privacy Commissioner External Link

Financial rules

Depending on the nature of the incident, your organisation may have legal obligations to notify the NZX, shareholders, or other relevant authorities. Be familiar with the requirements that apply to your sector.

International laws

While less common, your organisation may be subject to international legal obligations – particularly if you operate globally or hold data from overseas customers. Make sure you understand these in advance, so you’re not caught off guard.

Internal policies

Your organisation may already have agreements or obligations in place with partners, suppliers, distributors, or unions about how to communicate during significant events. These can help shape your messaging by clearly defining what must be disclosed – and to whom.

Cyber insurance

If you hold cyber insurance, you will likely have specific reporting requirements under your policy. Your insurer may also provide support for external communications and stakeholder updates – check what services they offer before an incident occurs.

How to create a message

“Organisations that take responsibility and are seen to be proactively trying to address the problem are perceived in a positive light.”

– Richard Knight and Jason Nurse [2]

This part of the process can be daunting – but being transparent builds trust. If stakeholders first hear about the incident from the media, they’re more likely to react negatively.

Messaging tips

When creating the messaging for external communications, you’ll need to cover a lot of ground – while keeping things clear and easy to understand. It’s also important to explain what’s happening and what the next steps are.

- Strike a balance between sharing clear, helpful information and protecting sensitive details that could be misused or escalate the attack.

- Avoid saying anything you may need to retract or correct later.

- Assume everything you say to stakeholders could be reported to the media – treat it as public messaging.

- The media may contact you before you’ve had a chance to notify stakeholders. Be prepared.

How people react to cyber incidents

People are more likely to act on cyber security when they hear about real incidents. Research shows that one in four people are more likely to improve their online security after hearing about a cyber attack. [3].

This matters when you’re communicating during an incident. If people know something has happened, they’re more likely to:

- take action to protect themselves,

- be cautious about clicking on links,

- treat unfamiliar email addresses with suspicion, and

- try to confirm your message through other sources.

Don’t set up a new email address just for incident communication – it can look suspicious or fake. Send your message through the channels your audience already trusts. It’s okay if the message comes from someone senior, like your CEO, but make sure it’s delivered in a familiar way.

Balancing the message

You’ll need to clearly explain what happened and what’s being done – but keep in mind that your communication could also be seen by the attacker.

That’s why it’s critical to work closely with your incident response team. Early information gathering helps shape the right message for the situation.

- What type of incident occurred? This helps set expectations for timing and impact. It also informs what details can be shared.

- Is the incident ongoing? If it is, or if you’re unsure, keep your messaging cautious and stick to the facts. It’s safer to assume the incident is ongoing until you know otherwise. [4]

-

What actions have been taken? Share enough to build trust, but avoid tipping off the attacker.

-

Are other organisations involved? Mentioning external experts or government agencies (if appropriate) can improve confidence – but remember, organisations like the NCSC do not confirm their involvement publicly.

Example scenario

An attacker has exfiltrated data and deployed ransomware. Your incident response team has isolated one server and is cleaning others. Restoration from backups is underway, and a ransom demand has been received.

Your message should contain some, but not all, of that information.

“Our incident response team is working to contain the issue and secure any unaffected systems. We are aware that some data may have been stolen and are working to ascertain the extent of that. We have notified the Office of the Privacy Commissioner and will keep them updated as the situation progresses.”

Controlling the message

You’re not required to respond to every media query. But refusing to engage or downplaying the situation can mean losing control of the narrative.

Have some pre-prepared, generic media statements ready, to be sent as a full press release or through social media. Even a placeholder is better than silence.

Example statements

“We are aware of a disruption with our systems, and we are looking into the cause.”

“We are aware that some of our online services are currently down, we are working at getting them back up as soon as possible.”

While these statements may sound generic, they show that you’re aware of the issue and acting. But as the incident continues, they won’t be enough – you’ll need to provide more detail as the situation develops.

Avoid framing cyber attacks as minor glitches or unexpected tech issues. If you stay silent, journalists may turn to third-party sources, which can lead to misinformation.

Order of communications

The type and severity of an incident will determine who you need to contact and when. The more visible or serious the incident is, the sooner you’ll need to release a message.

Stakeholder risk and visibility matrix for cyber incidents

- Highly visible to the public, but low risk to stakeholder data.

Use a written statement or media release. Timing may depend on the scale of the outage. - Highly visible to the public, and high risk to stakeholder data.

Communicate early but cautiously. Start with a short message, then expand. Use brief, carefully worded media responses. - Low visibility to the public, and high risk to stakeholder data.

Notify stakeholders as soon as the incident is discovered. Public messaging can come later, if needed. Continue monitoring for changes. - Low visibility to the public, and low risk to stakeholder data.

No immediate communication may be needed. Consider a post on your website or social media.

Any message, including internal ones, could become public. Write everything with that in mind.

Internal communications

Once the incident response team is active, internal staff should be informed.

Depending on the incident, include:

- what internal systems are affected (for example, email or logins),

- how staff should engage with customers or the public,

- whether staff data may be at risk, and

- what support services are available.

External stakeholders

If external stakeholders are affected, contact them as soon as it’s appropriate to do so. Your message should explain:

- what external-facing systems are affected,

- what data may be at risk, and

- how stakeholders can get support or more information.

Keep messages simple and factual. You may also need to scale up your contact centre or add extra support staff.

Communications are typically sent by email, but physical letters may be needed depending on your audience.

Some people prefer to talk to a real person. Be ready to provide a phone number or help line.

Media release and queries

Public-facing incidents often require a media response or press release. However, never issue a press release before you’ve informed affected stakeholders.

Allow at least one business day between stakeholder communications and public media engagement to account for delivery delays.

You are not obligated to issue a press release. If the story hasn’t already surfaced, there’s no need to amplify it.

People are less likely to trust your organisation if they hear about the incident from the media before they hear it from you.

What to say in your message

This is one of the most important parts of your response. Your message needs to be clear and concise – but also empathetic. Some of the advice in this section might seem basic, but we’ve seen organisations get caught out by these common traps.

A good message gives stakeholders the information they need to protect themselves. It also shows that yourorganisation is taking the situation seriously and doing everything it can.

The subject line

If you are contacting people by email, your subject line needs to stand out – without sounding alarming or too generic. It should reflect the urgency of the situation without creating panic.

Remember: people get a lot of emails. If your message doesn’t look relevant or important, it might be missed.

Accept responsibility

You are the kaitiaki – the custodian and caretaker – of your stakeholders’ data.

Even if the incident was caused by a third party or a software flaw, your stakeholders will expect accountability. That means offering a clear and sincere apology

Apologise to people not just about the situation.

- Don’t say: “We are sorry that this incident makes you feel vulnerable.”

- Do say: “We apologise to those who feel vulnerable in light of this news.”

- Don’t say: “We are sorry to say that there was a data breach.”

- Do say: “We have discovered a data breach and apologise immediately to all affected.”

Even if the issue was caused by something a stakeholder did (like reusing a password), people still expect you to have systems in place to help prevent or detect problems early.

Avoid downplaying

Minimising the impact of an incident – even unintentionally – can make it seem like you’re not taking it seriously.

Avoid words like “only” or “just” when describing the scale of the incident. This also protects you in case the scale grows.

- Don’t say: “The incident only affected 100 people.”

- Do say: “The incident was limited to 100 people.”

Address feelings of vulnerability

Some incidents may make people feel exposed or unsafe – especially when personal information is involved.

Let people know what they can do to protect themselves. Suggestions might include:

- contacting their bank, the NCSC, or the Office of the Privacy Commissioner,

- changing passwords on affected accounts, or

- turning on multi-factor authentication.

If financial data was involved, consider offering free credit monitoring or fraud protection.

People may be reluctant to click on links in your message. Make sure your advice is clear, even if they don’t follow a link.

Avoid blaming others

Pointing fingers – even subtly – can make your organisation seem defensive or untrustworthy.

This includes blaming:

- individual employees (even if their actions contributed to the issue),

- service providers or software providers, and

- known attacker groups.

If others were involved, handle those conversations privately. Public blame damages trust and can hurt both organisations’ reputations.

Keep the message clear and easy to understand

Break the information into short paragraphs and plain language. Avoid jargon or long, formal words – for example, use “use” instead of “utilise”.

You might need to include some technical details. If so, keep them simple and provide a link to a more detailed explainer if needed.[5]

Don’t damage your credibility

Avoid saying things that you might later have to walk back.

For example, don’t say:

- “It’s a technical issue” when you know it’s a DDoS attack, or

- “No data has been breached” before the investigation has been completed.

Oversimplifying can make it seem like you don’t have a full response plan. If you can include extra details without compromising your message, do so.

Consider your audience

Different stakeholder groups will respond to different formats and messages.

- Some may not check email regularly but are active on social media.

- Some may ignore password advice unless they understand why it matters.

Add context where you can. For example: “Because your email and password have been taken, the attacker could try to access other accounts. You can protect yourself by changing your password and turning on multi-factor authentication”.

Other organisations

If other organisations are affected by the same incident, consider issuing a joint statement. This can make it clear that you weren’t targeted alone and may help you share resources.

Beyond the message

Your message will likely prompt follow-up questions – even if you think you’ve answered everything.

Make sure your team, especially those who deal with external stakeholders, are well briefed. Prepare a list of key messages and common questions with suggested responses, so they can answer consistently and confidently.

What to do after the event

Updates

Depending on the type of incident and how long it lasts, you may need to send updates. Keep these short and focused on what’s essential. If an investigation is still underway, stakeholders will expect updates as new information becomes available.

You don’t need to send updates if there’s nothing new to share. You can set the expectation in your first message – let people know you’ll only follow up if there’s something important to report. Just make sure that approach fits the nature and severity of the incident.

Also be aware that the situation could change. Some incidents – like a DDoS attack – may flare up again. Attackers might also attempt a second strike if they think you’re still vulnerable. Be ready to respond if that happens.

Debrief

Every incident is a chance to improve. Once things have settled, review how your communications went. Talk to internal and external stakeholders to understand what worked, what didn’t, and how you can do better next time.

Self-assessment

After an incident is a good time to review your communication systems and processes. This might include:

- checking and updating stakeholder contact lists,

- improving internal reporting lines, and

- reviewing your website’s incident messaging or frequently asked questions (FAQs).

Your incident response team will look at the technical side – you should focus on what needs to change from a communication perspective.

Footnotes

[1] 'Richard Knight and Jason R.C. Nurse, 2020, A Framework for Effective Corporate Communication after Cyber Security Incidents, Computers & Security Journal, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2020.102036 External Link , https://kar.kent.ac.uk/82836/ External Link

[2] 'A Framework for Effective Corporate Communication after Cyber Security Incidents', Richard Knight and Jason R. C. Nurse, 2020

[3] 25% of respondents said they are more likely to implement online security after hearing a cyber attack story – 'Cyber Change: Behavioural insights for being secure online', CERT NZ, 2022, pg42-43

[4] If it is uncertain if the incident is ongoing, treat it as such.

[5] Cyber Change: Behavioural insights for being secure online, CERT NZ, 2022, pg31-32

Social media and website updates

Social media and your website are valid channels for communication – especially low-risk incidents. They can be used alone or alongside a press release, depending on the scale and visibility of the event.